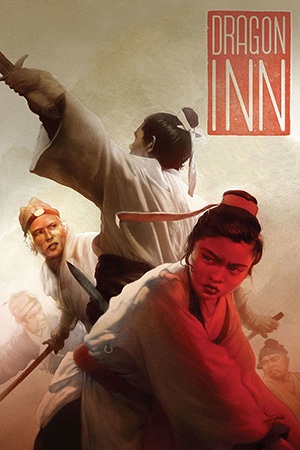

Along with ‘Come Drink With Me’ and ‘A Touch Of Zen’, ‘Dragon Inn’ is perhaps King Hu’s most admired work. Hugely esteemed within the swordplay genre and a noted inspiration to directors of the Hong Kong ‘New Wave’, it remains a film that enjoys a certain reputation at home and abroad. After years of existing only in a heavily butchered VCD print, two DVD releases have breathed new life into this milestone work.

Heinous eunuch Zhao is the Machiavellian power behind the Chinese throne, ruling the land through fear and intimidation. The one threat to his position, royal executioner Yu, is executed after being convicted on trumped up charges and his family are exiled to the farthest reaches of China. Paranoid Zhao still fears the influence that Yu’s family could have with the rebel cell within the government and decides to slaughter them before they reach their destination. A small troop of soldiers is sent to the isolated ‘Dragon Inn’ – located in the most inhabitable reaches of the wilderness – to intercept the remaining Yus and they take over the location in preparation. Despite attempts to secure the inn and stop any casual visitors entering, no-one is able to prevent phlegmatic swordsman Xiao from waiting for his friend, the inn keeper Wu, from making the place his temporary abode. The loyalist warriors try to flex their muscles in front of Xiao to scare him off, but when this fails they dedicate their efforts to finding out what his real motives are. Tensions are heightened when a brother and sister also lodge at the inn and seek to ask awkward questions about the delicate situation around them. As events move to a frenzied conclusion, Zhao elects to journey to the distant outpost in an attempt to cement his evil plan.

The action may have dated, but King Hu’s renown will only increase after one of his most noted works is finally given the treatment it deserves. Full of his trademark directorial parsimony and concentration on utilising the environment as if it were a major character in the film, ‘Dragon Inn’ retains much of the presence it exuded on its initial release. King Hu’s regard for the atmospherics of chanbara cinema is noticeable throughout this production and the director proudly shows how the skills left by the great Japanese film-makers can be given a Hong Kong identity.

As with his later ‘Fate Of Lee Khan’, Hu builds the story up layer by layer and allows that subtle sense of disquiet to seep into the frame. This is particularly striking when the battle is fought with words rather than the somewhat antiquated swordplay that slightly undermines the story’s conclusion. The dialogue between Xiao and the general Pi adds a frisson to the proceedings that makes their climatic duel far more exciting than the choreography allows; the deceitful ‘friendship’ the two act out throughout the first hour of the film is an intelligent way to lay the ground work for later conflict and help make this much more than just a standard swordplay flick. That, essentially, is what separates King Hu from so many other directors who have attempted a work in this genre: Hu takes the actual crafting of the story and the characters as seriously as any other element of the production. Hu’s performers are not just there to replicate the actions set out by an unseen action choreography, they are to act and give the well written characters he screen life they deserve.

The environment is always vital to Hu’s work and the use of a claustrophobic setting ensures that ‘Dragon Inn’ retains that quality. What is ingenious about the location here is that it is essentially an insular, taut set – complete with requisite cabin fever setting in – placed within a vast inhospitable hinterland. Such an extreme contrast lends itself well to Hu’s aims with the film and his intention to let the mood of the picture be as important as the other components. The cinematography enforces this juxtaposition and serves as the perfect framework for the drama to unfold.

‘Dragon Inn’ doesn’t quite compete with ‘A Touch Of Zen’ and ‘Come Drink With Me’, but anything to be criticised here is a mere niggle rather than a detrimental flaw. It stands the test of time and is further evidence of a director who deserves a worldwide re-appraisal, hopefully one that would note what a significant artist he was. Until that day comes, Hong Kong film buffs can finally appreciate the work of King Hu for all its manifold qualities.

- A Guilty Conscience - February 26, 2024

- River - February 12, 2024

- Perfect Days - January 31, 2024