Like many others, my only previous viewing experience of this final chapter in Liu Chia-Liang’s 36th Chamber trilogy was a fairly dreadful VHS print taken from a Japanese print. The story – hindered by incomprehensible subtitles – became a mere side issue that I could only guess at while the action was barely watchable. It was therefore of great interest to me when Celestial announced that this would be in their first year of releases and of course presented in a typically exceptional remastered print. So, the final part in this rightfully acclaimed series is finally able to be subjected to a proper review by myself.

The opening of the film – making atmospheric use of Shaw Brothers’ soundstage – shows talented young fighter Fong Sai Yuk (Hsiao Hou) in the various confrontations that made his name famous. After this, though, the focus is on Fong’s troublesome antics at school as he bullies the teacher while his two brothers struggle to keep him under control. Despite complaints from his teacher, Fong manages to avoid a severe reprimand from his father due to his ever-loving mother’s (Lily Li) timely intervention. Nevertheless, Fong Sai Yuk’s supercilious attitude means that he continues to ruffle the feather’s of the authorities – much to his father’s chagrin. One of his actions proves to have significant consequences though as Fong, unhappy with the Ching dominance, starts a brawl in a Ching army gymnasium and only just manages to escape thanks to his brothers’ help. The Chings refuse to let the matter pass and discover Fong’s whereabouts, then give his parents an unpleasant ultimatum: Hand over the troublesome urchin or the local Cantonese school will be shut down. With such a dilemma facing them, Fong’s parents are forced to send their son to the Shaolin temple so that he can hide, though there’s also the hope that he will learn some disciple as well. The ever cocky Fong Sai Yuk finds the disciplined lifestyle and repetitive training beneath him and clashes with famed monk San Te (Liu Chia-Hui) on more than one occasion. In his desperation to be free of Shaolin’s regulations, the young fugitive escapes the temple at night and returns to the relative glamour of the city. When he attends a Ching-run Lantern festival he makes an unusual friend in the shape of a local governor (Pai Piao) who seems very eager to learn about Shaolin’s 36th Chamber. Naive Fong cannot see the trap he’s slowly falling into when his new ‘friend’ invites him and his Shaolin colleagues to a Ching wedding, supposedly to unify the two contrasting peoples.

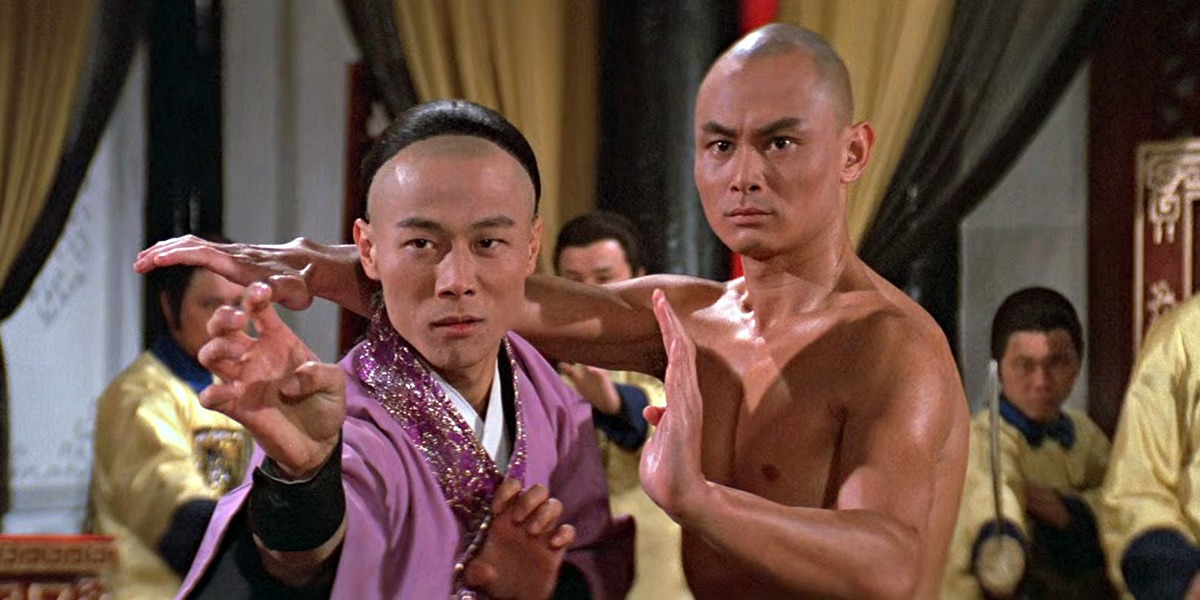

After creating one of the genre’s greatest works with ’36th Chamber of Shaolin’ and following it up with an unrelated, yet wonderfully entertaining sequel, Liu Chia-Liang cemented his relationship as a kung fu auteur with few peers. Although this conclusion to the trilogy isn’t on par with its forerunners, it still provides even the most spoilt viewers’ with a collection of exceptionally choreographed set-pieces – more on this later. Liu Chia-Hui returns to the role that will always define him – San Te – and eases back into the role with such professionalism that it seems there was never a gap between the first and third films. Whether he’s calmly lecturing his co-stars or fighting with the villains, Liu’s performance is a reminder of how powerful his screen aura was. What will undoubtedly attract many Shaw Brothers’ fans is the chance to see Hsiao Hou as Fong Sai Yuk; this acrobatic performer had precious little opportunity to show-off his legendary skills in most of his other roles, but here Liu Chia-Liang shines the spotlight mainly on him. The part of Fong Sai Yuk in this film appears to be an obvious template for Jet Li’s later triumph in the role, but it is this characterisation that is one of the main problems here. Hsiao Hou is always a joy to watch when he’s fully utilised, but the actual character of Fong proves to be a little too arrogant for the good of the film. His hot-headed antics cause countless destruction and harm to his friends and family, though he barely seems moved by it all – a trait that becomes increasingly annoying. With a hero who loses sympathy as the film goes on, Liu Chia-Liang is almost paddling against the tide and things aren’t helped by an all-too-common storyline. For one of the genre’s great innovators to rely on stereotypes and clichés that occur without any imagination is a troubling aspect of this otherwise praiseworthy movie.

‘Disciples Of The 36th Chamber’ is, as indicated above, not one of the film’s that would solidify the claim of many (myself included) that Liu Chia-Liang is kung fu’s Kurosawa. However, it is thankfully imbued with a good quantity and tremendous quality of intricately choreographed fight action. Performed with flair and invention, the film benefits hugely from a few stand out skirmishes; the brief, yet exhilarating bench fight ranks among these as does the chaotic finale that features some very complicated sequences. Although Liu Chia-Hui and Hsiao Hou are naturally impressive, Jason Pai Piao is also worthy of a mention – though his fights are limited, he has a fine mixture of abilities that make him a fine antagonist for the film. ‘Disciples Of The 36th Chamber’ is a quality film; from the choreography to Liu Chia-Liang’s artistically composed frames, this is a more sophisticated kung fu film. A cut above the rest it might be, but there’s little doubt that Liu Chia-Liang has made better films.

- Carry On Doctors And Nurses - January 6, 2026

- Fight For Tomorrow - December 21, 2025

- Mission Kiss And Kill - December 7, 2025