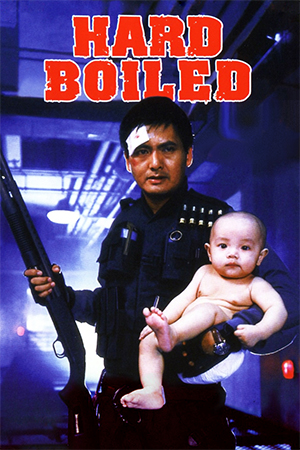

The entry point to the Heroic Bloodshed genre for many British lovers of Hong Kong cinema, ‘Hard Boiled’ still delights an amazing twelve years after it was made. It was also John Woo’s Dear John… to the Hong Kong film industry and by 1993 he was stateside with ‘Hard Target’, and has not yet produced an English language film to match his Cantonese classics.

But, while Hollywood compromised him, John Woo allowed his imagination and cinematic showmanship full flight in ‘Hard Boiled’, strapping his trademark visuals and themes to an RPG and launching them into orbit.

Yep, we’re talking favourite films here so only superlatives will do. I am also assuming that fans of DDUK are very familiar with the film so this review contains spoilers.

In 1989 Woo had raised the bar of Hong Kong action cinema with ‘The Killer’ after setting it with his brace of ‘A Better Tomorrow’ films. With ‘Hard Boiled’ he clearly wanted to make ‘The Godfather’ of action movies; a film that so perfectly realises its ambitions it would become a point of comparison for any other genre offering.

Like ‘The Killer’, ‘Hard Boiled’s plot is a straightforward story of honour and friendship, loyalty and betrayal. Chow is supercop Tequila, obsessed with tracking down arms traffickers in Hong Kong. After a classic opening teahouse fire fight, in which Tequila kills a key trafficker in revenge for a fallen fellow officer, he sets his sights on Johnny Wong (Wong), arms dealer number one and a fully fledged psycho to boot.

Wong has recruited Tony (Leung), a hotshot hitman, and makes him prove his fealty by assassinating his boss, Mr Hoi (Kwan), an archaic crime lord bound by a code of honour. Unbeknownst to Johnny or Tequila, Tony is an undercover agent also attempting to break the arms dealing ring. As with ‘The Killer’ the two finally unite, taking the battle to Johnny and his arsenal of weapons concealed hidden in a hospital. Here begins one of the most beautifully handled action scenes in cinema history, lasting an incendiary thirty minutes.

For the growing number of Woo detractors underwhelmed by his American films (and for Anthony Wong who derided Woo as just another action director, reportedly because he was angered at Kuo Chui’s villain being given the same status as his), ‘Hard Boiled’ is the ultimate riposte and a scintillating display of his directorial power.

Woo directs with the zeal of a dying man completing his one last masterwork, which is not far from the truth. From the opening teahouse gunfight (a reference to past Wong Fei Hung films and HK’s action film legacy?) John Woo revels in the language of film, directing with the energy his inspiration Martin Scorsese applied a year earlier to ‘GoodFellas’. Woo uses deep backgrounds and extreme close ups to set the scene, tracking amongst the protagonists and antagonists, effortlessly establishing who is who. He also pays homage to Sam Peckinpah, another key influence, with expert use of slow motion to punctuate the action and accentuate the impact. Even step printing, ubiquitous in HK action cinema at the time, is brilliantly used to convey wounded movement.

The opening teahouse scene and the climactic hospital conflagration are so intensely mounted and memorable ‘Hard Boiled’s other action sequences are frequently overlooked. But, the warehouse action scene contains some of the film’s most amazing stunts and is bracketed by Tony Leung’s stellar performance.

Acting is often overlooked in Hong Kong action movies, dismissed with a sniff that these films are undisciplined copies of more respectable Western, or even mainland Chinese or Japanese cinema. While Chow Yun Fat is the charismatic star of the film, Leung offers the most compelling performance. His boyish good looks frequently clouded by guilt and doubt, Leung offers a tour-de-force of conflicting emotion as he massacres to curry favour with Johnny. ‘Hard Boiled’ for many was an introduction to Chow and Leung, but also to Wong and Phillip Chui, who memorably plays Mad Dog, Johnny’s lethal, though honour-bound, right hand man. Watching Kuo as the hero of numerous Shaw Brothers movies, or as a sympathetic friend in ‘Lady in Black’, means trying to forget his formidable performance here. Wong too, despite his bad mouthing, is unforgettable as Johnny, icy cold with ambition and greed. Takashi Miike fans will also spot a cameo from Jun Kunimura in the teahouse scene, and Woo himself pops up at Tequila’s jazz bar owning mentor.

Woo pushes his actors to express the pinnacles of emotion, and while this robs his films of subtlety it crucially lends weight to his spectacle. And Tequila’s one-man army assault on Johnny’s men in the warehouse is an awesome spectacle. Maybe the scene is often overlooked because a warehouse is a conventional setting for an action scene, and the teahouse and hospital are fresher to Western eyes. But, the warehouse holds many treasures; explosive stunts with motorbikes, stuntmen (and main actors?) consumed by explosions, and an exclamation mark courtesy of a trademark Woo visual, the two leads face-to-face, guns temple to chin.

Logic is frequently defied as Woo’s cinematic swagger turns plot contrivances into directorial élan. Echoing ‘The Killer’, Tequila investigates a hit executed by Tony and is seemingly telepathically drawn to the hollowed-out volume of Shakespeare (a master of revenge and violence) in which Tony’s murder weapon was concealed. Cries of “As if!” are beside the point, Woo’s aim is to emphasize the bond his central characters share.

Woo repeats this flamboyant act for the climax, as Tequila’s girl (Mo) finds a flower in her pocket at exactly the right time to begin the evacuation of the patients. Realism is not John Woo’s watchword, and he proves ostentation works wonders in a film with character and heart.

‘Hard Boiled’ has been accused of lacking the emotional core of ‘The Killer’. While the film’s only female character is sidelined until the finale ‘Hard Boiled’ is awash with emotion. The problem may be that Tequila is less interesting than the morally compromised Tony. While Tony is trapped between two worlds and forced to jettison his principles, Tequila is a square-Joe myopically pursuing justice and that is never as riveting.

But, the film contains those frissons of unabashed sentiment that mark Woo’s best work. For storytelling and character development ‘The Killer’s key scene is the shoot-out on the beach when Ah Long has to rescue a young girl caught in the crossfire. ‘Hard Boiled’ riffs on this moment frequently in the final thirty minutes, as innocent civilians frequently stray into the paths of bullets, and reaches a giddy zenith as Tony and Mad Dog locked in a deadly duel, lower their guns when a huddle of frightened people come between them. Shockingly, Johnny then mows them down.

The slaughter of civilians in the hospital and the teahouse is not merely cynical carnage. At the time of the film’s release Woo revealed ‘Hard Boiled’ was his statement on the 1997 handover of Hong Kong. The hospital is a metaphor for what he believed Hong Kong would become in five years time, a place of crime and open gang warfare where civilians would live and die in fear. When Tequila and Teresa are spiriting the babies out of the hospital, they are literally preserving the future of Hong Kong. Thankfully, this crimewave does not seem to have occurred and Hong Kong actually has a very small number of firearms.

Thematically rich, ‘Hard Boiled’s climax also stands as a masterpiece of planning and execution. Woo, ably assisted by action director Kwok (credited here as Cheung Jue-Luh), delivers a brilliantly sustained sequence that wracks up the tension and repeatedly outdoes itself. All that Woo has given to action cinema is here: the double Beretta leap through the air, the Mexican standoff, the gleefully preposterous close quarter gunfire played as a dance of death, thousands of squibs, the reflective pauses of the two leads who yearn for an impossible new dawn. The sheer exhilaration of this denouement plays havoc with the audience, traversing a map of emotion from excitement to tension to shock, and finally, as Tequila leaps from the exploding building with baby in hands, utter elation.

The cliché has become to describe Woo’s action as balletic, but music in ‘Hard Boiled’ is used in so many ways. Beyond the dated though exciting main action theme (that still works the same way ‘The A-Team’ theme does), Woo casts Tequila as an accomplished musician, who makes music with a clarinet as well as a handgun. Tequila’s bluesy playing often complements Tony’s tortured soul searching, and in another nice connection between the two protagonists Tony also makes music, sending his lieutenant (Chan) song lyrics containing hidden communiqués. Tony sends these in bouquets of flowers and sharp eyed viewers will notice Tequila holds a book about flowers when he investigates Tony’s hit near the beginning of the film. The climax also begins when Teresa discovers the rose in her pocket.

Is ‘Hard Boiled’ the perfect film then? Of course not, those wanting flaws will find them: as previously mentioned, Tequila is carried by Chow’s immense charisma, Tony’s method of smuggling a gun into a hospital is lifted from ‘Terminator 2’ (despite what other reports say to the contrary; there are shots replicated from Cameron’s film), and a gunfight on Tony’s boat seems to have been taken from Michael Mann’s pilot for ‘Miami Vice’. The film lacks a proper female role, Phillip Chan is the ball-busting chief of a thousand cop movies, and some audiences find the emotive force behind Woo’s bullet festivals overblown and off-putting.

But, let the naysayers pick over the latest John Woo disappointment, this is an unabashed love letter to Woo’s most accomplished directorial outing and his last truly great hurrah for chivalry.

- Web Of Deception - June 25, 2015

- Vital - June 22, 2015

- Visible Secret - June 22, 2015