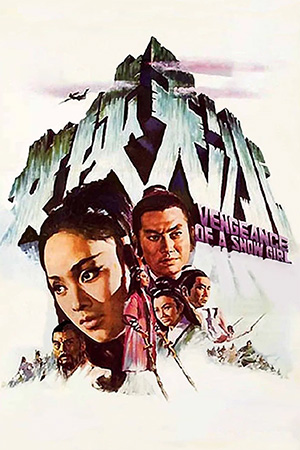

During mid-period Ming Dynasty a child emperor* is installed when his long serving predecessor passes away, which allows for corrupt Prime Minister, Jia Shou Dao, to play shadow ruler. Vocal critic of his oppressive measures, Song Yuan, Senior Lecturer of the Imperial Academy and tutor to the emperor, is imprisoned as an anti-government rebel. That leaves Chief Judge, Geng Shang De (Fang Mian) rushing to Song’s family with advice of an imperial pardon that was left to him by the late emperor. Song’s wife (Chen Yen Yen) and daughter (Li Ching) elect to disguise themselves as street entertainers and make their way to the capital with the pardon, whilst nephew Jin Shi Kai (Chan Leung) heads to the Prime Minister’s mansion with plans to avenge his uncle.

Unbeknownst to Song’s wife and daughter, the Prime Minister has sent the (similarly corrupt) Commander of the Imperial Guard, Gao Si Xian (Wang Hsieh), along with his deputies Ma (Fan Mei-Sheng) and Niu (Wang Kuang-Yu) and a small platoon, to stop them before they can overturn his incarceration. By chance the pair befriend wandering swordsman You Ru Long (Lo Lieh) along the way, who in turn becomes their shadow protector on the journey. Overhearing the offer of a valuable reward for their capture, Imperial labourer Hu San (Wei Ping-Ao) plots a plan of action. When Song’s family end up in the ‘Valley of the Fangs’ all parties intersect in what promises a deadly showdown.

Retrospectively exploring the vast array of genres and films from the expansive Shaw Brothers catalogue (commercially unavailable until 2002 when Celestial Pictures bought a sizeable chunk of the library and released them to the public via home video and subscription cable services) can produce myriad different reception to the studio’s output. Seemingly, for every dusty lump of coal akin to ‘Call to Arms’ (1972) there is an unsung, or undiscovered, gem such as Cheng Chang Ho’s enjoyably entertaining ‘Valley of the Fangs’ (1970). With two years to go before Cheng’s own ‘King Boxer’ (1972) would change the landscape, and the sword-fighting wuxia swashbucklers that appeared in the latter half of the sixties still very much in vogue, the region’s cinematic fortunes very much hinged on the genre’s box office capacity. Though few could hold a candle to such influential works as King Hu’s ‘Come Drink with Me’ (1966) or Chang Cheh’s ‘One Armed Swordsman’ (1967) and ‘Golden Swallow’ (1968) every once in a while an enthusiastic B-lister like ‘Valley of the Fangs’ took an energetic stab (excuse the pun) at riding on the wake of their successes.

Benefitting greatly from Korean import Jeong Chang-Hwa’s (under Chinese alias Cheng Chang Ho) tight, efficient direction and Japanese import Tadashi Nishimoto’s (under Chinese alias Ho Lan Shan) rich cinematography, ‘Valley of the Fangs’ separates itself from its peers by not bogging itself down with political intrigue and instead merely functioning as a straight-forward, rousing adventure opus. The plot is literally a race for the capital, with corrupt officials nipping at the protagonists’ heels, beset by various colourful stops along the way. True to the period, this means the inclusion of a couple of musical numbers in the Huangmei/folk style, with Li Ching (award-winning star of Kao Li’s ‘The Mermaid’, 1964) taking centre stage to entertain an inn full of patrons with a ballad referencing Chinese folk-heroine Hua Mulan, and the rotund Fan Mei-Sheng entertaining with a bawdy ditty of his own. There is also a welcome thread of humour that permeates the film throughout, most particularly in the subtle (by Chinese standards) comic relief on offer within the film’s spirited action sequences.

Of which, Lau Kar-Wing’s (incorrectly identified as Lau Kar Leung in some sources; Liu Chia Yung being the Mandarin variation of Lau’s name) action choreography really gives proceedings a qualified boost of vital energy to the production’s numerous fight scenes. There is a wire-work aplenty on display, albeit much more polished and less awkward than previous attempts at the art, and the climactic battle between Wang Hsieh and Lo Lieh (alongside the men of the Imperial Kiln in the valley, inclusive of Cheng Lui of ‘Magnificent Trio’, 1966, and Tung Li of ‘The Black Tavern’, 1972, against Wang’s small army) is definitely thrilling of its kind. There’s a little bit of playful fun to be had too when it comes to the various martial arts masters testing each other’s abilities, inclusive of Lo Lieh juggling cups of wine and showing his adversaries some amusing skills with deadly darts and coins.

From opening credits that ape the Spaghetti Westerns of the period to its surprising epilogue wrap-up (being that the majority of Shaw martial arts films finish the instant the villain expires), ‘Valley of the Fangs’ is an equally surprising and unexpected hidden gem. Offsetting the de-rigueur soundstages with lush, picturesque outdoors location work Cheng’s film presents as way vaster in scope than it is, much to its advantage. Throw in a beautiful young ingénue with Li Ching and a handsome, noble hero with the always dependable (as well as, sadly, late) Lo Lieh plus the ever-reliable Wang Hsieh as the surrogate villain and you have some solid first-class grounding. Strong direction, a steady pace, ravishing photography and incendiary action choreography only add to the mix. Thereby, if one can track it down I’d more than recommend this adventurous little swashbuckler as an impressive example of what the Shaw studios could achieve, even with a second-run feature, when they were at the top of their game pre-unarmed combat era.

Footnote (*): Though not explicitly stated, and governed by the fact that film is largely a work of fiction set within an historical era, research would indicate that the central governmental intrigue portion of the plot appears to derive from the documented history of Ming Dynasty emperor Zhu Qizhen (1427 – 1464). Zhu initially ruled as the Zhengtong Emperor from 1435 through 1449. Like his cinematic counterpart, he was a child emperor (appointed at eight years of age) and relied heavily on those around him to advise on matters of state (primarily chief eunuch, Wang Zhen – who has a screen counterpart in Tsai No’s character, briefly featured in the film’s introduction)