When Xiang Rong’s (David Chiang) father is killed in a traffic accident he’s left with the responsibility of caring for his mother and ensuring his sister completes her schooling. Recommended by best friend Gen Lai (Ti Lung) to local shop owner Fong (Chiang Nan), Rong quickly takes up residency as the new delivery boy. Two years pass in the blink of an eye and Rong has fallen off the path somewhat, regularly shoplifting from his employer as well as skipping deliveries to catch up with his circle of fellow sneaky shop stewards. He’s also caught the eye of neighbourhood beauty Lin Xiu Ping (Wan Man) but the two never seem to find time for one another.

Looking for some direction, Rong takes up kung fu classes at the local martial arts school under Master Yuan Hsiao Tieng (Yuen Siu-Tien), but is expelled in less than a year due to his headstrong nature and pent-up aggression. Chance brings him across former delivery colleague Stone (Chiang Tao) and in turn shady businessman Tou Cheng (Lo Dik). Tou is impressed with the fiery youngster when he almost bests his bodyguards, King Ren (Eddy Ko) and Liu (Lee Hoi-Sang), in a show bout and offers him a job within his organisation. Though the money is beyond his wildest dreams in his days as a delivery boy, Xiang Rong soon realises that his new employment is well outside the law.

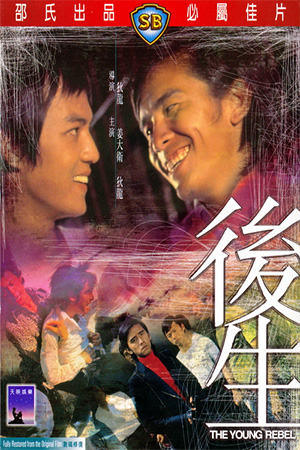

Throughout the early-to-mid seventies the combined pairing of Shaw superstars David Chiang and Ti Lung together in a film was a virtual licence to print money and box office receipts attested the fact spectacularly. Being that Chiang had cast Ti as his lead in his directorial debut, ‘The Drug Addicts’ (1974) the previous year, Ti returned the favour by picking Chiang to headline his second directorial outing, ‘The Young Rebel’ (1975). And a fine little youth drama-come-morality play it is, with screenwriter and director Ti taking a leaf out of mentor Chang Cheh’s books from the earlier juvenile dramas (oft erroneously referred to as “juvenile delinquent” dramas) akin to ‘Young People’ (1972) and the award-winning ‘The Generation Gap’ (1973). Essentially, Ti has taken the traditional tale of a chivalrous hero’s journey of self-discovery and awareness and dressed it up in (then) contemporary clothing. By avoiding the usual tropes of the genre Ti skilfully guides the viewer through his contemporary urban drama without their awareness of its origins until well after the fact.

A long way from the fading memory of the 1967 riots (which made for a fascinating backdrop of the much later, and exceptionally accomplished, romantic drama ‘A Fishy Story’, 1989) and some years on from the 1971 introduction of the government subsidised education scheme, the fortunes of Hong Kong were on the rise. Even the widespread reality of police, and governmental, corruption had come under fierce scrutiny with the establishment of the ICAC (Independent Commission Against Corruption). Thus, with the turbulence of the sixties gone and allied involvement in the Vietnam conflict at an end, public concerns over organised crime and its influence on the region’s youth still made excellent fodder for popular cinema. Within Chiang’s working-class everyman, Ti deftly creates a metaphor for many of those concerns as well as the ideal that said youth might be able to rise above those that would manipulate them and make morally-defining decisions for themselves.

Moral fibre, integrity and values are what screenwriters Ti and Ni Kuang (who wrote the majority of the Shaw’s biggest hits as well as created Wisely, adventurer of the fantastic) deliver in abundance with ‘The Young Rebel’, albeit without overstating their message with phony moralising. Chiang’s Xiang Rong is, essentially at heart, a young man of a good disposition with a set of core values seeking direction in his life, and it is the lure of money and life on easy street that inevitably is his undoing. There are no harsh judgements made, no familial histrionics over Xiang Rong’s choices, just a simple story of two childhood friends and the different paths their lives take (as the film opens at its end with Xiang in the custody of his friend, Gen Lai, now a police cadet, and is told in flashback by way of explanation of how he ended up where he is when the story begins).

It’s plain old-fashioned greed that motivates Xiang Rong as, when given the choice between food and lodging plus a HK$50 allowance per month for hard work over HK$3000 with no questions asked other than to be on call, his decision isn’t a difficult one. And once he discovers his youthful sweetheart, Lin Xiu Ping, working as a see-through waitress in a seedy club (during a drunken bender) that becomes the pivotal decider towards his descent wholly into a life of crime. Of course, Ti’s character of Gen Lai attempts to keep him on the straight and narrow by introducing the discipline of martial arts training into his life, but even teacher Yuen Siu-Tien (later to find considerable global fame as Jackie Chan’s sifu in Yuen Woo Ping’s ‘Drunken Master’, 1978) ends up cutting him loose, citing his inability to control his anger his main stumbling block. With a pair of pointy ears, one can almost envision Yuen reciting the Yoda mantra: “…anger leads to hate, hate leads to suffering…”

Obviously, the introduction of the martial arts element leads to an inevitable array of action sequences, and with no less than three action choreographers onboard (Liu Chia Yung/Lau Kar-Wing, Huang Pei-Chih and Chan Chuen) viewers can be assured of some frenetic set-pieces. However, though the fight scenes are prolific, Ti wisely introduces martial arts as a plot element and not the plot itself. Through his affinity for Chinese kung fu Xiang initially learns something of self-discipline, then uses it as a strong-arm into Tou’s organisation, and ultimately harnesses it as a means of escape from his wayward criminal life. Xiang’s martial prowess is more akin to street-fighting than the traditional styles of the Shaw’s period epics and there’s as many brutal kicks to the groin delivered as there are elbows to the face. It’s all exceptionally well captured by cinematographer Kuang Han-Lu (‘The One-Armed Swordsman’, 1967) too, as well as (the film in general) given an earthy realistic texture.

In summation, it’s a pity that Ti Lung didn’t venture behind the camera more throughout his career as, with this film and the previous year’s ‘Young Lovers on Flying Wheels’ (1974), he showed quite a flair as both a storyteller and a filmmaker able to capture both the stark realism of his settings and the colour of his characters. Compatriot Chiang, of course, went on to direct several other features during his career, eventually returning to the strong anti-drug sentiment of his debut feature with ‘Will of Iron’ (1991). Star spotters should get a kick out of spying sneak cameos from action directors Lau Kar-Wing and Chan Chuen, alongside favourites Hsu Hsia, Fung Hak-On and Yen Shi Kwan as well as brief spot by a young Sammo Hung as an illegal back-alley gambler. Though the overly moral message may deter some, there’s more than enough rough and tumble scraps to entertain fight fans and a host of strong performances from the leads as well as a thoroughly involving story to engage most everyone else, making ‘The Young Rebel’ fine entertainment.

Originally published on Hong Kong Rewind © 2011, M.C. Thomason

- My Name Is Nobody - March 12, 2021

- Girl$ - December 4, 2020

- Seeding Of A Ghost - August 7, 2020