What’s your favorite Haruki Murakami adaptation? Over the last forty years, there have been only a handful of choices to consider, a list that includes Kazuo Imori’s ‘Hear the Song of the Wind’ (1981), Jun Ichikawa’s ‘Tony Takitani’ (2004), Tran Ahn Hung’s ‘Norwegian Wood’ (2010), Daishi Matsunaga’s ‘Hanalei Bay’ (2018), and Lee Chang-dong’s ‘Burning’ (2018). Of these initial five films, I hold ‘Tony Takitani’ and ‘Burning’ in high esteem. Both honor their source material while also offering original interpretations that take Murakami’s ideas in exciting new directions. For example, the two main actors in ‘Tony Takitani’—Issey Ogata and Rie Miyazawa—play dual roles, immediately altering the way we perceive their respective characters, while the setting of ‘Burning’ moves the events of the short story “Barn Burning” from Japan to South Korea, resulting in a complete reinvention of the characters and their motivations. In 2021, the sixth addition to the list of Murakami film adaptations arrived in the form of Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s ‘Drive My Car’, which went on to win three awards at the Cannes Film Festival including Best Screenplay. While employing very different methods than his directorial predecessors, Hamaguchi offers yet another original take on Murakami, one that rivals and perhaps even surpasses them all.

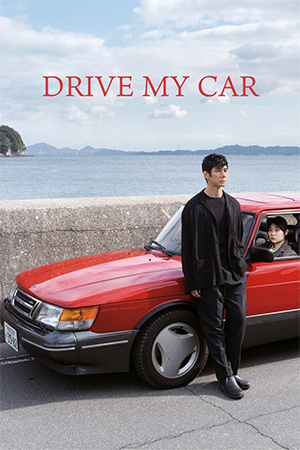

In truth, ‘Drive My Car’ is both a beautiful adaptation and a clever expansion of Haruki Murakami’s short story of the same name from the 2014 collection ‘Men Without Women’. Through the extended metaphor of driving, Hamaguchi crafts a subtle and involving examination of the various blind spots, car crashes, detours, and dead ends that we all must face on the road of life. Ultimately, ‘Drive My Car’ is a film about the search for a reason to keep going—all without an intended destination in sight or our preferred travelling companion beside us.

The film’s prologue could exist as an involving drama all on its own. In this extended pre-title sequence, the focus is entirely on the relationship between theatre actor-turned-stage director Yusuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima) and his TV writer wife Oto (Reiko Kirishima). After several decades together, the two have settled into a comfortable, intimate, and—by all appearances—committed marital existence. But nothing is quite what it seems.

One fateful day, Kafuku returns home unexpectedly and stumbles upon Oto in the middle of a sexual tryst with TV actor Koji Takatsuki (Masaki Okada). Rather than make a scene and confront his wife about her infidelity, our protagonist quietly retreats, fleeing their apartment and never once broaching the subject. The mental anguish of maintaining the façade of normalcy eventually catches up to Kafuku, resulting in an unexpected traffic collision. While Kafuku emerges uninjured from the car accident, his doctor diagnoses him with glaucoma—a literal blind spot that takes on significant metaphorical implications.

At the end of the prologue, after various opportunities, Kafuku has the perfect chance to confront the figurative blind spot in his marriage when Oto tells him point blank that she needs to talk. However, by the time Kafuku returns home for their planned heart-to-heart, he finds his wife’s body on the floor. Whatever she intended to tell him will remain forever unsaid, as she dies of natural causes. Throughout the prologue, the theme of communication—whether direct, indirect, or unspoken—becomes increasingly prominent.

The film then jumps ahead two years with the now-widowed Kafuku arriving in Hiroshima to put on a multilingual production of Anton Chekhov’s ‘Uncle Vanya’. To protect their investment, the theatre company hires the stoic Misaki Watari (Tōko Miura) to chauffeur Kafuku around Hiroshima in his red Saab 900. The tentative, quietly emerging friendship between passenger and driver serves as the beating heart of ‘Drive My Car’. Although more than a few male protagonists in Murakami’s work find their lives changed by mysterious, worldly women or preternaturally wise young girls, Hamaguchi has no interest in reducing Misaki to a cliché. If anything, the director stays true to Murakami’s description of her character in the short story, while also deepening her inner life and providing a backstory that is both tragic and wholly believable. Misaki is quietly proficient at her job, incisive in her observations, and yet deeply wounded by life in ways that match Kafuku’s own secret scars.

As a point of reference, ‘Drive My Car’ shares narrative DNA with ‘Tony Takitani’ (both the short story and the film), as they each deal with a widower who must come to terms with both his spouse’s sudden death and the aftermath of her impulsive behavior—a shopping addiction in the case of ‘Tony Takitani’. Both characters go to great lengths to deal with their grief. In ‘Tony Takitani’, the title character attempts to hire a personal assistant but with the condition that she wear all his wife’s unworn clothes as a uniform. In ‘Drive My Car’, Kafuku casts Oto’s former paramour as the lead in ‘Uncle Vanya’, despite being obviously unsuited for the role. Is Kafuku attempting to torture his former rival? Or is he trying to find out what his wife saw in the guy beyond his youthful good looks? Or does our protagonist harbor an unconscious desire to mold Takatsuki into a respected actor in his own image? Whatever his intentions, Kafuku never really tells us, and his experiment turns out to be as doomed as Tony Takitani’s, although not for the reasons you might expect.

But even if we leave aside the uneasy master-apprentice relationship between Kafuku and Takatsuki, the film’s “play-within-a-play” structure is rich with meaning. First, it should be noted that Kafuku’s version of ‘Uncle Vanya’ is performed by actors who communicate in Japanese, Mandarin, Korean, Tagalog, and even Korean Sign Language. However, the cast members do not understand each other and must practice daily to learn the rhythms of their peers; in fact, if they have any questions about the text, they must communicate through a third-party intermediary. Thus, Kafuku’s staging of the play explores the limits of true understanding while also suggesting that genuine moments of connection can transcend language or even the spoken word. The cast’s desire to connect with one another parallels not only the interactions between Kafuku and his taciturn driver but also several moments he shared with his late wife. Before Oto’s death, she attempted to admit her guilt by describing the strange plot of a TV drama she was writing. However, her ostensible confession came to nothing because Kafuku refused to probe any further, despite possessing some inkling of what lay hidden beneath her cover story.

Hamaguchi also uses ‘Uncle Vanya’ to comment on the very nature of art itself. Despite being associated with the title role, Kafuku refuses to play the part of Vanya for the Hiroshima production. The experience of inhabiting that character is grueling for him, and some of the lines hit too close to home in the wake of his wife’s infidelity and death. Without spoiling the outcome of this particular plot thread, ‘Drive My Car’ is also very much about how the medium of art (as either a creator or a consumer of it) often makes us come face-to-face-with bitter truths about our lives, ones that we would normally shy away from—and how that can be a scary, even dangerous proposition for our psyches. However, the experience can also be therapeutic and ultimately valuable, but only if we are willing to take the risk. Yes, sitting down to watch a movie is a leisure activity that can provide viewers with a much-needed feeling of escapism, but in the end, we can never really escape ourselves.

All told, ‘Drive My Car’ runs just shy of three hours, but it feels so much shorter. Despite the many details I have dropped, this review only scratches the surface of what the film has to offer. To give one brief example, supporting actor Park Yoo-rim delivers a moving performance as a deaf actress in ‘Uncle Vanya’, and an unexpected detour involving her character provides an alternative pathway in life for both Kafuku and Misaki to admire—and perhaps emulate. Beyond this, there are additional secrets, both big and small, to be uncovered. In the end, Ryusuke Hamaguchi proves himself to be as skilled a director as Misaki is a driver. To paraphrase a line from the film, the experience of watching ‘Drive My Car’ was so smooth that I forgot all about the three-hour run time, the other people in the theater, or the very fact that I was watching a movie at all. I just sat back and enjoyed the ride. Maybe you will, too.

- Fish Story - December 10, 2021

- Drive My Car - November 21, 2021

- Parasite - July 12, 2019